Probiotics for Immunity

Immunity is a vital function of the human body for the maintenance of good health. One of the most startling revelations to emerge over the past few decades has been the role of the gut microflora in all aspects of immune function. We all play host to populations of micro-organisms that live in and on our body. These populations are made up of trillions of bacteria, yeasts, and even parasites or viruses. Some of these micro-organisms work to help the body systems; some are benign, and some are actually detrimental to health, but whatever their effects, the majority of these little passengers like to live in our intestines where there is a plentiful supply of food sources for them.

Within this article:

- What’s that now? Our resident bacteria ‘talk’ to our immune system?

- Are some probiotics more beneficial for immunity than others?

- Probiotics and the immune system - in-depth

What's the connection between these invisible multitudes and our immune system? Well, the first thing to appreciate is that around 70% of our immune system is thought to be located in our intestines, so it’s no surprise that most healthcare practitioners maintain that ‘good health starts in the gut’. Therefore, if you are trying to improve your immunity, then it would seem to make very good sense to keep intestinal health in optimum condition, and evidence suggests that probiotic bacteria play a key role in this4. You can read more about this connection in the Probiotics Learning Lab: Probiotics: the best way to support your immunity

But what is even more interesting is that emerging research suggests our resident gut bacteria actually 'communicate' with our immune system and help to ensure that it responds appropriately.

What’s that now? Our resident bacteria ‘talk’ to our immune system?

Incredible as it may seem, the answer to that is ‘Yes! A review of the available research, conducted in 2015 and published in the journal Frontiers of Immunology1, concluded that our probiotic bacteria, in particular, our gastrointestinal microbiota (one of the names for our resident populations of micro-organisms) played a significant role in the immune responses of humans and all other vertebrates:

“The presence of microorganisms within any vertebrate, from fish to humans, plays a significant role in the development of immunity and further capacities on disease resistance and health status along life.1”

The review goes on to explain that gut dysbiosis could potentially have ‘profound physiological and metabolic consequences at local and systemic levels’. Hmmmm…that really brings home how important it is to keep digestive function in tip-top order, and evidence suggests that one of the ways to keep your gut health may be to consider supplementing with probiotics, in conjunction with a healthy diet and lifestyle2. But if you particularly want to improve and support immune function, do certain strains of bacteria offer particular benefits for immunity?

Are some probiotics more beneficial for immunity than others?

The principle underpinning the majority of probiotic research is based on the concept that different strains work in different ways (see Probiotics Learning Lab), and certainly the available research appears to indicate that this principle also extends to immune function.

A recent report in the Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology reviewed the potential of probiotics for allergy prevention and concluded that:

“The probiotic performance of strains differs; each probiotic strain is a unique organism itself with specific properties that cannot be extrapolated from other, even closely related, strains…Therefore, research activities are currently focusing on identification of specific strains with immunomodulatory potential.6”

Clinical research in humans is the most definitive test of the efficacy of any substance, and there are some very convincing clinical studies which indicate that certain strains of bacteria may be superstars when it comes to supporting our immune system. You can read more about this research in our fabulous educational resource, The Probiotics Database, a compilation of the world's most extensively-researched probiotic strains, where you can also see strains which have been particularly researched for immunity.

Undoubtedly, one of the most researched probiotic strains for immunity is Lactobacillus paracasei CASEI 431®, which has been shown to reduce the duration of cold and flu symptoms by three days, compared to placebo, in a gold standard flu vaccine challenge study9. You can read more about the research that supports all of these strains on the Probiotics Database.

If you're interested in finding out more about exactly how probiotics work with the immune system, then read on...

Probiotics and the immune system - in-depth

Here we look at;

- How do probiotics interact with our immune system?

- Probiotics and innate immunity

- Autoimmune responses

- Probiotics and adaptive immunity

- Probiotics – a key tool for immunity?

How do probiotics interact with our immune system?

It seems weird to think that such tiny organisms could influence our health, working with our bodies in synergy for a mutually beneficial relationship. But it’s in the interests of our resident bacteria to keep their hosts in tip-top shape, and this symbiotic relationship may have evolved because bacteria naturally did what was necessary to keep their ‘homes’ safe.

Our immune system is made up of several different areas all working together in order to address the innumerable threats to which our bodies are constantly exposed: physical injuries, pathogens in the form of harmful bacteria and viruses, toxins, foreign bodies, stress, anxiety, fear etc. In order to cope with this seemingly endless myriad of enemies, the immune system is divided into separate areas: the innate immune system, and the adaptive immune system which encompasses humoral immunity and cell-mediated immunity.

Our innate immune system is our oldest, inherited weapon in our immunity arsenal, thought to have been in its current form for 500 million years. It’s a system that we share with most other living organisms, including plants, and its strength lies in ‘barriers’, such as skin, hairs, mucous membranes, and inflammatory processes, where immune cells are sent to sites of infection or trauma. The innate immune system has a very limited 'memory' and adaptive potential, however, so will harness its sister system, the adaptive immune system, when unknown 'enemies' or new situations present.

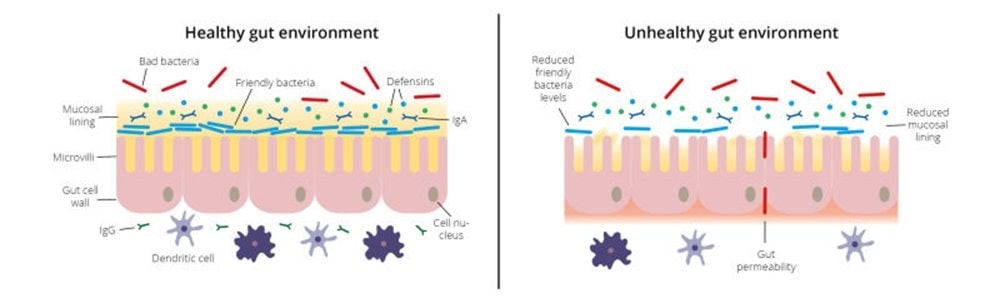

A review of the available research, published in the journal Frontiers of Immunology1, concluded that our commensal bacteria had the potential to work as an integral part of the whole immune system: by rebalancing dysbiosis (imbalance of good and bad bacteria), displacing pathogens, increasing production of antimicrobial peptides and mucins, helping to strengthen mucosal barriers and modulating cell-mediated immune responses. You can read more about the interaction between the gut microbiota and immune function in this article: Gut bacteria play key role in immune function

Probiotics and innate immunity

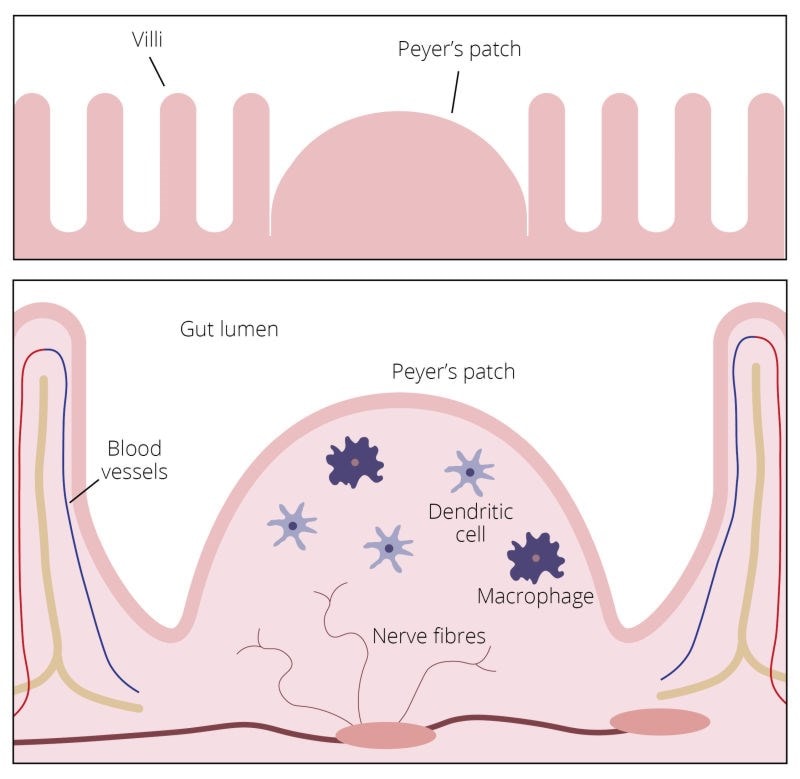

As the mucosal tissues of the mouth and the gut wall comprise some of the most important ‘barriers’ involved in innate immunity, then it’s fascinating to learn that the tiny residents of these areas can significantly influence the integrity of our immune function1. As previously mentioned, at least 70% of our immune cells are located in the gut, housed in structures buried in the delicate hair-like villi which cover the intestinal wall. These structures, called Peyer's Patches, contain a variety of immune cells including B cells, T cells, macrophages and dendritic cells, and are involved in both innate and adaptive immune function.

If the integrity of the gut wall is compromised, this can lead to ‘inappropriate’ immune responses that we know as ‘allergies’. See Kathy's great blog post on this subject over in the Probiotics Learning Lab: 'Gut Bacteria, Allergies, and Probiotics'.

Probiotics may help to mediate allergy symptoms in a number of ways. They may help to improve the integrity of the intestinal lining, preventing permeability of the tight junctions in the epithelial wall caused by Tumor necrosis factor alpha 5 (TNFα). TNFα is a cytokine, a cell signalling protein involved in the acute inflammatory processes that can be initiated by pathogenic microbial infection, and this process acts to damage the epithelial lining, creating permeability. This permeability allows larger protein molecules to pass through the intestinal wall and into the bloodstream, where they are seen as unnatural ‘predators’ that can stimulate a further aggressive inflammatory response that we know as an ‘allergy’.

So probiotics are thought to help to alleviate and prevent this situation by displacing the pathogens that originally cause the inflammation and by helping to promote the secretion of anti-inflammatory mediators involved in the healing process.

Some strains of live cultures show particular promise in these areas; for example, an in-vitro study published in the journal Physiological Reports 5 indicated that both Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus appeared to offer great potential in preventing intestinal permeability and reducing inflammatory responses. The probiotic bacteria were shown to prevent epithelial barrier disruption induced by TNF‐α, and promote wound repair. Friendly bacteria like Lactobacillus paracasei CASEI 431® have also been shown to help improve immune function by strengthening and tightening the tight junctions which seal the intestinal lining.10

Autoimmune responses

In some cases, the immune system turns on itself, manifesting as a large and indistinct cluster of diseases known as ‘auto-immune diseases’. Poor gut health is being linked more and more to the development of auto-immune diseases, so early intervention - potentially including the use probiotics - is thought to be helpful, as they can influence the type of responses that occur.

It’s worth remembering when you’re trying to support patients with autoimmune disorders, however, that because the probiotics DO have an interaction with the immune system, they are sometimes contraindicated in those where immune function is extremely weak and unpredictable. See, over in the Probiotics Learning Lab, When should I NOT take probiotics? for more information on this.

Autoimmune conditions are believed to be associated with intestinal permeability, or 'leaky gut', and so those strains believed to help with intestinal repair, such as L. paracasei CASEI 431® and Saccharomyces boulardii are often used by practitioners as part of a gut-healing protocol for their clients. For more information about leaky gut, and how probiotics might help, read Kathy's blog: Probiotics and Leaky Gut.

Probiotics and adaptive immunity

The adaptive immune system is like the ‘brains’ of the innate immune system; innate immune function is more of a ‘one size fits all’ response with a limited memory, whereas adaptive immune responses are far more sophisticated. This is the arm of the immune system that produces specifically tailored-responses to incoming antigens, which it then ‘remembers’ long-term in case they come calling again. There are two types of adaptive responses: one is known as a cell-mediated immune response, and the other is known as the humoral immune response. The cell-mediated immune response uses activated T cells, whereas the humoral response removes those pathogenic microorganisms which have not penetrated body cells and requires various antibodies to be produced by B lymphocytes.

Emerging evidence suggests that probiotics can influence the orientation of the adaptive immune response and the production of cytokines, signalling messengers which tell immune cells how to behave and respond, and different strains of bacteria appear to prompt either pro or anti-inflammatory cytokines to be produced. This illustrates the importance of strain specificity when choosing a probiotic. The immune system in the gut learns to recognise 'friend' from 'foe' in the populations of gut bacteria; in fact, beneficial bacterial have been shown to help to prompt the production of immune cells, and regulate the production of the antibodies they produce as part of the humoral immune response, such as sIgA, IgG, and IgM3,11.

The cell-mediated arm of the immune system kicks in when incoming pathogens enter a cell and infect it, requiring it to be engulfed by phagocytes such as macrophages, which then present the identity of the pathogen on their cell wall for identification and destruction by T-helper and T-killer cells. Pathogens can hide out and multiply both inside and outside bodily cells but are attacked and captured by antibodies produced by B-cells, paving the way for killer T-cells and macrophages to finish the job if necessary. In this way, the immune system prevents infections from spreading throughout the body, and amazingly, our microbiota has been shown to influence the production of these antibodies and other defensive cells3. Probiotic strains, such as L. paracasei CASEI 431® have been shown to inhibit the growth of pathogens, upregulate the production of antibodies, and modulate cytokine secretion11.

Probiotics – a key tool for immunity?

The gut microbiome can be regarded as a metabolically active organ and modulation thereof by probiotics or prebiotics is becoming increasingly recognized as an important therapeutic option.1”

So great is the role being identified for the gut microbiota in our health, that it is becoming widely regarded as an ‘organ’ in its own right, an 'organ' which appears to play a key role in immune function. Of course, more research into this area is essential, as probiotic mechanisms of action in this area, and many other areas of health, are still not fully understood, but the emerging evidence is continually highlighting the importance of our invisible armies of bacteria in the maintenance of good health. As always, we'll be keeping a close eye on emerging evidence, but these are certainly exciting times for probiotic research!

For more on the subject of probiotics and the immune system, see some of our other blogs here:

Bifidobacterium bifidum Rosell-71 reduces colds in new study

A look at zonulin and leaky gut syndrome

References

- Montalban-Arques A et al (2015) Selective Manipulation of the Gut Microbiota Improves Immune Status in Vertebrates, Frontiers in Immunology. Oct 9;6:512. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2015.00512. eCollection 2015.

- José E. Belizário* and Mauro Napolitano (2015),Human microbiomes and their roles in dysbiosis, common diseases, and novel therapeutic approaches, Frontiers in Microbiology. 2015; 6: 1050. Published online 2015 Oct 6. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2015.01050

- Pagnini et al (2010) ‘Probiotics promote gut health through stimulation of epithelial innate immunity’ Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010 Jan 5; 107(1): 454–459. Published online 2009 Dec 29. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0910307107

- Fang et al (2000) Modulation of humoral immune response through probiotic intake. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2000 Sep;29 (1):47-52.

- Chen‐Yu Hsieh et al, (2015) Strengthening of the intestinal epithelial tight junction by Bifidobacterium bifidum, Physiological Reports Vol. 3 no. e12327 DOI: 10.14814/phy2.12327

- Isolauri E, Salminen S, (2008), ‘Probiotics: use in allergic disorders: a Nutrition, Allergy, Mucosal Immunology, and Intestinal Microbiota (NAMI) Research Group Report’, Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology. 2008 Jul; 42 Suppl 2:S91-6. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e3181639a98.

- Leyer GJ, et al. (2009) Probiotic effects on cold and influenza-like symptom incidences and duration in children. Official Journal of the American Academy of Pediatrics; Vol. 124, pp. 172-179

- Laboratory analysis, Unique Biotech Ltd.,Hyderabad

- Rizzardini G. (2012), ‘Evaluation of the immune benefits of two probiotic strains Bifidobacterium animalis ssp. lactis BB-12® and Lactobacillus paracasei ssp. paracasei, Lactobacillus casei 431® in an influenza vaccination model: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled study’, British Journal of Nutrition, March, 107(6):876-884.

- Christian Hansen proprietary unpublished data

- Galdeano CM1, Perdigón G.(2006), The probiotic bacterium Lactobacillus casei induces activation of the gut mucosal immune system through innate immunity. Clin Vaccine Imm

Popular Articles

View all General Health articles-

General Health25 Sep 2023