Stress & Bloating

We've all had that feeling of being stressed and know the accompanying sensation of unease in our gut well. Anyone who is familiar with IBS, food intolerance or cravings, will no doubt know how strongly our gut can influence our mood. What a lot of people might not realise is that it’s a two-way street, and stress and emotions can also trigger common digestive complaints like bloating. As we slowly start to ease our way out of Covid-19 restrictions stress levels could be running high, navigating the ‘new normal’ and reintegrating back into work and society. Read more about the link between the microbiome and mental health.

Within this article:

- Can anxiety or stress cause stomach pain and bloating?

- The ENS (Enteric Nervous System)

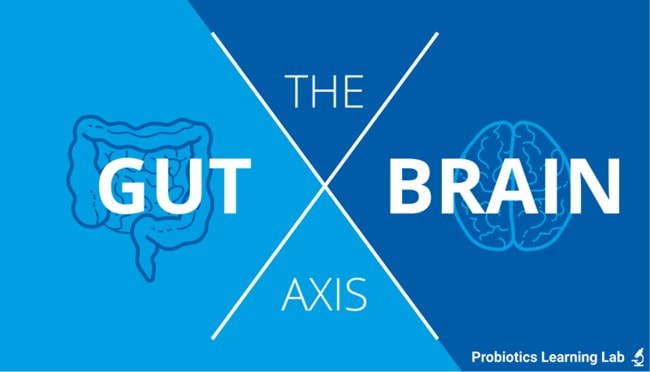

- The Gut Brain Axis

- The 'Fight or Flight' Response

- Can probiotics help?

- Improve gut health naturally

Can anxiety or stress cause stomach pain and bloating?

Essentially, when you're feeling anxious or stressed, your brain goes into a ''Fight or flight'' mode and stops your body from properly digesting food until things get back to ''normal''. However, when you're in a stressed state for a long time you never fully come out of that ''Fight or Flight'' mode, which means your digestive system is always compromised and symptoms of digestive upset such as bloating may occur. Continue reading to find out what is happening in our gastrointestinal tract when we are stressed.

The ENS (Enteric Nervous System)

Within the gut, or more specifically within the lining of the gastrointestinal tract, is a complex network of nerves known as the enteric nervous system (ENS)1. The ENS is in charge of keeping the gut organised and functional, essentially working as the gut's brain. Unlike other systems the ENS is able to independently send and receive information, record experiences and respond without having to involve the brain and central nervous system (CNS)2, the nerve system for the rest of the body.

However, both systems are cooperative and in constant two-way communication. For example the CNS recognises the sight or smell of food triggering the ENS to produce saliva and digestive enzyme secretion. On the other hand, the ENS provides the CNS with information letting us know when we're hungry, bloated or in pain. Made up of similar cells and utilising many of the same neurotransmitters, research continues to show that both the ENS and CNS are heavily influenced by one another.

The Gut Brain Axis

The gut-brain connection is a fast-growing area of research within the scientific community. An important factor in the relationship between the gut and the brain is serotonin, a CNS neurotransmitter that is involved in psychological well-being and happiness. We’ve found that over 90% of the body's serotonin (also referred to simply as our ‘happy hormone’) is found within the gut, where it is involved in peristalsis (the involuntary muscular action of the gut), secretion and sensation.

Some 50% of the body's dopamine (another neurotransmitter, involved in motivation and arousal) alongside ‘building blocks’ of other important psychoactive compounds including enkephalins (natural opioids or pain relievers) and benzodiazepines (relaxants similar to Valium) are also found in the gastrointestinal tract4. Due to a number of reasons (increased demand, nutritional deficiencies, inflammation, etc.) alterations in the concentration or function of these chemicals will influence both the central nervous system (affecting mood) and the enteric nervous system (affecting digestion).

Abdominal symptoms frequently occur in those with conditions associated with the CNS such as depression, anxiety disorder, migraine, epilepsy and autism. With many of the drugs used to treat these conditions also producing gastrointestinal side affects5. Read more about the link between gut health and autism.

Vice versa, psychological distress is often linked with gastritis, ulcers, IBS and inflammatory bowel disease. With stress also widely thought to contribute towards many common gut disorders including gastritis, food intolerance and celiac disease6.

In short, distress in either the CNS or ENS appears to adversely affect the other.

The 'Fight or Flight' Response

The digestive system is particularly susceptible to stress as the CNS essentially shuts down or slows down gastrointestinal function via the ENS when there is a perceived threat. The body responds to stress by producing stress hormones which rapidly increase our physical and mental ability to deal with the dangerous situation. During this state of hyperarousal, processes such as digestion that aren't essential for physical exertion are repressed in favour of those which focus on dealing with the stressor.

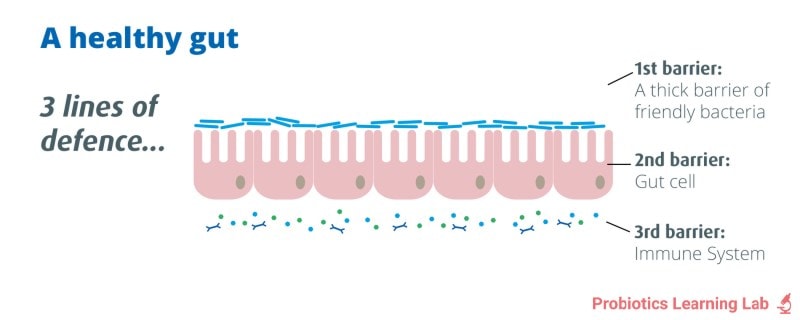

Blood flow to the gut, intestinal motility, intestinal permeability, digestive enzyme production and protective mucus secretion are all affected7 by stress. This is why anxiety and bloating often go hand in hand. When stressed and anxious, many experience sensations such as: butterflies in their stomach, nausea, a choked up feeling, trouble swallowing, indigestion, heartburn and perhaps even diarrhoea.

When the stress or danger that we are facing is short-lived, the stress response's brief inhibition of digestion is of little concern as normal function returns once the perceived threat has passed. However, with chronic or ongoing stress the digestive system remains subdued, making it difficult to digest food effectively, predisposing not just the gut, but the entire body to problems8.

Poor digestion and nutrient absorption; heartburn; bloating, cramps; weakening of the intestinal wall's barrier function; altered bowel function and changes in the number and composition of gut microbes (also known as dysbiosis), can all occur as a direct result of prolonged stress. An imbalance of beneficial and harmful bacteria can be helped by taking probiotic supplements, which is looked at later on in this article.

Can probiotics help?

Certain strains of probiotic bacteria have been specifically researched in gold standard clinical trials and shown to be effective at reducing symptoms of stress and anxiety. Strains such as Lactobacillus acidophilus Rosell-52 have shown benefits for both stress and bloating. Therefore, it is always worth doing a little research before starting a new supplement. It's important that you select one that is clinically proven to be effective for your own personal health requirements, whether that is probiotics for bloating, stress or something else.

To read more on this topic, you may like to visit the following article: Probiotics for stress.

Health professionals can learn more about the research into L. acidophilus Rosell-52 over at the Probiotics Database:

Improve gut health naturally

As already discussed, stress can cause bloating by stimulating the body's "Fight or Flight" response which negatively impacts gut health and impedes our digestion. So, if you experience symptoms of an unhealthy gut, such as indigestion, bloating, constipation, flatulence, cramps, diarrhoea or other gastrointestinal problems, it may well be worth investigating how your emotions and stress level might be contributing factors.

Research into the link between our gut health and our emotions has been plentiful during recent years, and scientists now know that this is a bi-directional relationship. In the simplest terms research has shown that our mood can affect our gut, but perhaps more importantly our gut health can most definitely affect our mood.

It is thought that the bacteria that colonise the human gut, may influence our emotions in several ways, including:

- production of neurotransmitters and hormones

- stimulation of the immune system

- Regulation of inflammatory pathways

- interaction with the vagus nerve (that travels between the brain stem and the gut).

Many people find that anxiety-reducing techniques help to relieve their digestive problems, whilst also helping them relax and even sleep better.

Helpful techniques include:

- mediation,

- exercise,

- yoga,

- qi gong,

- counselling,

- acupuncture,

On the flip side, by taking good care of our digestive system we get the benefit of better digestive health, whilst also creating a healthier gut-brain relationship and supporting our psychological well-being at the same time.

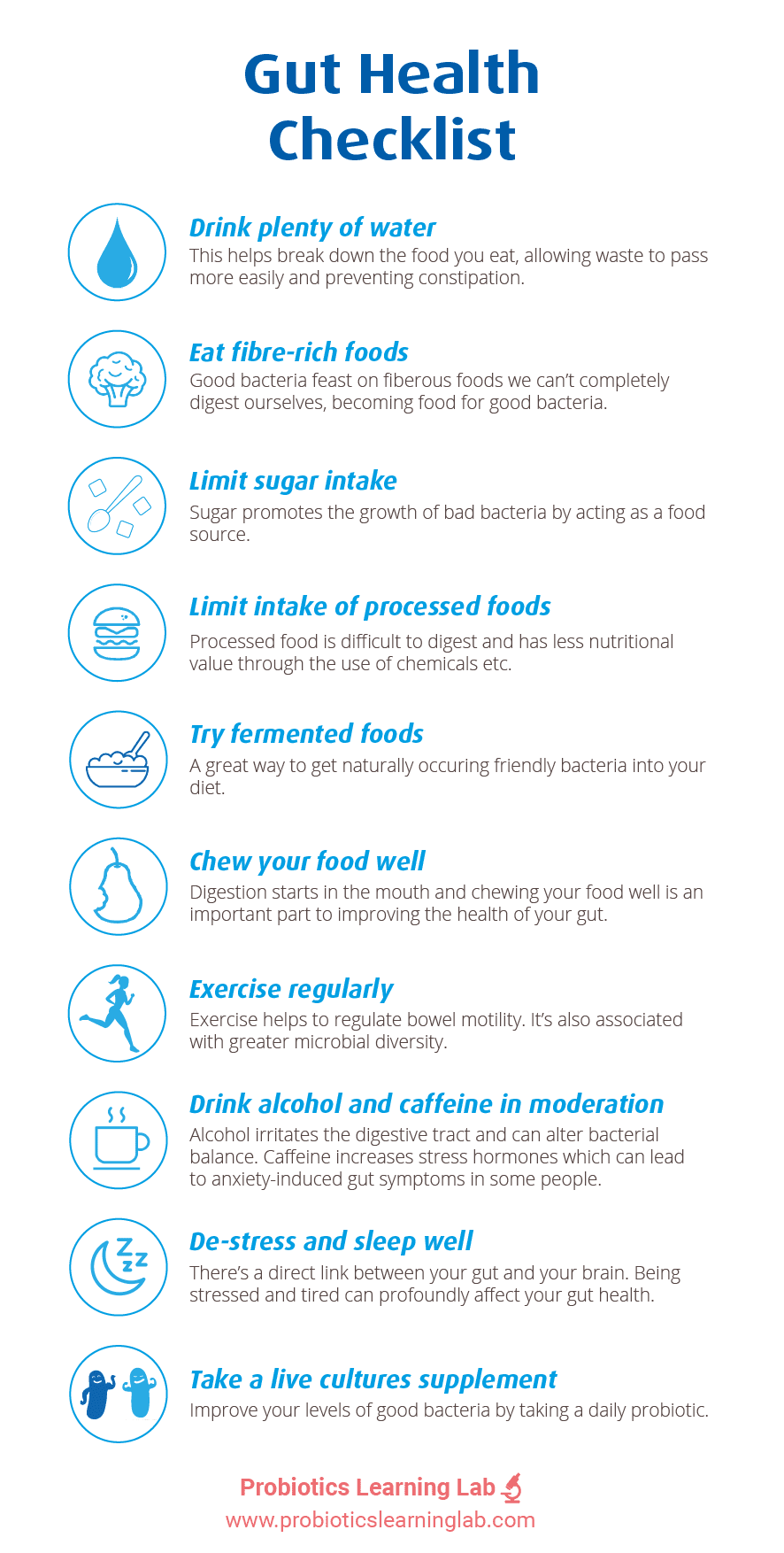

Simple steps we can take to nurture our gut, include:

- Reducing inflammatory foods in the diet (sugar, refined carbs, trans fats)

- Including healing herbs and botanicals (ginger, peppermint, rosemary, turmeric)

- Taking probiotics

- Including healthy omega 3,6 and 9 fats in our diet (from oily fish, olive oil, nuts, seeds, avocados etc.)

The below infographic shows our top tips for a healthy gut. And remember that it usually pays to trust those 'gut instincts'…

References

- Goyal, R., & Hirano, I., 1996, ''The Enteric Nervous System'', The New England Journal of Medicine, 344:1106-1115.

- Bunnett, N., 2005, ''The stressed gut: Contributions of intestinal stress peptides to inflammation and motility'', Proceedings of the national academy of sciences in the United States of America, 102(21):7409-7410.

- Williams, S., 2010, 'Gut Reaction: The Vibrant Ecosystem Inside the human gut goes more than digest food'', Howard Huges Medical Institute Bulletin, 14-17.

- Kim, D., 2000, ''Serotonin: A Mediator of the Brain-gut connection'', The American Journal of Gastroenterology'', 95(10), 2698-709.

- Horvath, K, et al, 1998, 'Improved social and language skills after secretin administration in patients with autistic spectrum disorders', Journal of the Association of Academic Minority Physicians, 9:9-15.

- Hertig, V., et al, 2007, ''Daily Stress and Gastrointestinal Symptoms in Women with Irritable Bowel Syndrome'', Nursing Research, 56(6):399-406.

- Palmer, S., 2000, 'Physiology of the stress response', Centre for Stress Management and City University, London, http://www.managingstress.com/articles/psychophysiology-of-stress-response

- Oxford Journal, 2000, 'The stress response and the hypothalamical adrenal axis: from molecule to melancholia' QJM: An International Journal of Medicine, 93(6):323-333.

Popular Articles

View all Mental Health articles-

Mental Health13 Feb 2024

-

Mental Health22 Nov 2023

-

Gut Health22 Dec 2023